On the thirtieth anniversary of her death at the hands of police, we present a poster in memory of anarchist and People’s Park defender Rosebud Abigail Denovo (RAD). Rosebud was a runaway hitchhiker, juvenile institution escapee, and anarchist. She was killed shortly after her nineteenth birthday while participating in the struggle for public commons in Berkeley, California.

Today, People’s Park is once again under attack. The University of California at Berkeley attempted to level the park on August 3; destruction is slated to resume in October. You can keep up with efforts to defend the park here.

Click on the image to download the poster. Poster courtesy of Privatelifeonline.

Rosebud, One of the People

In 1969, two clandestine lovers authored a call in a Yippie underground rag to turn the derelict, university-owned lot that they used for a romantic rendezvous into a park. A hundred people turned out the first day, and over the next month more than a thousand people—without permission or legal ownership—turned the lot into People’s Park by removing trash and putting in plants and art. Governor Ronald Reagan sent in troopers and cops to evict the “haven for communist sympathizers, protesters, and sex deviants,” killing one onlooker and injuring dozens more with buckshot and tear gas. In turn, park defenders tore down fences and resisted the police by throwing bricks at them and setting their cars on fire. Throughout the 1970s, people defended People’s Park by occupying it en masse whenever the university threatened to begin construction.

Footage from the origins of People’s Park in the 1960s.

While coincidentally squatting the same property that Ted Kaczynski had resided on as a University of California at Berkeley math professor in 1969, Rosebud threw herself into the defense of the three-acre park founded that same year.

People’s Park in the 1960s.

In 1991, riot police escorted bulldozers to tear down the park’s Free Speech Stage and build university volleyball courts. Rosebud was arrested for trespassing, vandalism, and attacking police officers in the ensuing defense. Days later, police raided her campsite, where they found a crossbow with arrows, a copy of The Anarchist’s Cookbook, and a diary entry addressed to the university chancellor: “[Y]ou’re not getting off that easy.”

Early in the morning of August 25, 1992, Rosebud used a blowtorch to cut through bars and break into the house of the chancellor of the university, setting off a silent alarm. Police entered the house and fatally shot Rosebud in the back. In one hand, like an anarchist from the era of propaganda of the deed, she carried a note demanding an end to construction in People’s Park: “We are willing to die for this piece of land. Are you?” In the other hand, she carried a machete.

Mourners clashed with police for a week after Rosebud’s death. The District Attorney declined to charge the cop that shot her.

Click on the image to download the poster in black and white. Poster courtesy of Privatelifeonline.

An Account from the Defense of People’s Park, August 2022

On August 2, 2022, just hours after court approval, UC Berkeley erected fences around People’s Park. In the still of the night, construction crews began felling trees. A tweet called people to go to the park and defend it.

At midnight on August 3, 2022, a mass text alert went out announcing that the University of California at Berkeley had began their preparations to seize People’s Park—and that they were expecting a fight for this historic revolutionary public space. UC Berkeley deployed their own police department in full riot gear to protect the contractors they had hired to build a fence around the perimeter of the park.

Park defenders face off with police early on August 3, 2022.

We arrived around 2 am, as People’s Park defenders were being arrested for laying their bodies down where the contractors were installing anti-climbing fences. By sunrise, there were perhaps twenty defenders and park residents left inside the park, facing off against over a hundred UC Berkeley riot cops, private security, social and community workers, as well as dozens of construction workers. Tree service workers waited on the side street behind a police barricade for the riot police to evacuate the defenders from the park.

The final dispersal was at 9:30 AM. Some park defenders took their last stand inside the old kitchen structure; only five remained inside the park, but UCPD entered the park with intention to carry out arrests. Slowly, the other park defenders were kettled outside of the fence by over 70 riot police in full riot gear wielding batons and dog catcher sticks. The defenders chanted, “Sacred land, sacred space, People’s Park must remain.”

This parent and child team participated in the defense of the park. Nineteen years ago, they planted the tree they are standing with here. During the assault on People’s Park, they watched as the university killed it.

Expert Tree Service entered the park and started clear-cutting it while the remaining defenders still remained on top of the kitchen. They took down 47 trees—including redwoods, cedar, cypress, oaks, and fruit trees, some trees older than the park and others planted in people’s honor.

More park defenders arrived to the sound of chainsaws, realizing what had happened while they slept. Private security tried to block all main roads leading to the park, but could not keep people from finding their way through. UC riot police attempted to form a line to keep park defenders back from the fences, brutalizing them with large steel batons; they, too, failed. The fence was finally breached and park defenders entered the park to protect the few remaining trees. At that point, the UC police retreated and Expert Tree Service vacated the park.

Soon, all the fences were completely down. With the space liberated, more community members arrived throughout the day bringing food, water, and medical supplies. By 5 pm, there was a rally on campus and a march in support of People’s Park. Hundreds of people showed up to support and listen to park defenders, some of whom have been defending the park for decades. Park defenders and supporters got to work cutting the felled trees to clear them to the perimeter. Comrades set up medical tables, brought in food, and erected tents that night for anyone who needed shelter. In the face of brutal neoliberal violence, a beautiful and powerful movement of community resistance emerged.

Four excavators that were left behind in the park were beautified. The fences were repurposed to defend a kitchen around a redwood still standing in the middle of the park.

The groups Make UC a Good Neighbor and the People’s Park Historic District Advocacy Group rushed to court that same day, asking for and achieving a stay of demolition on environmental grounds. Corporate news outlets report that construction is unlikely to resume until October, but the university has shown that it is ready to renew its assault on the park as soon as a court grants them permission.

The Present is a Gift Born from the Cataclysmic Conjuncture of Past and Future

For the past two years, participants in the Ex-Worker Podcast have been touring the globe to screen our documentary, We Are Now, chronicling the police-free zone that arose in response to the fatal police shooting of Rayshard Brooks in Atlanta during the George Floyd Uprising.1 For our tastes, there is no greater joy than being able to screen the film in the context of other autonomous, police-free territories in rebellion. When we learned that park-loving people had interrupted the felling of trees and the attempted development of People’s Park at the beginning of August, we had to check it out.

When I arrived, the park reminded me of a sparse Occupy encampment. There was an information table in the middle with Slingshot magazines on it; people were living in tents on one side of the park. Slain trees were strewn all over the area. The trunks of a dozen fallen trees, some over a century old, had been rolled to the perimeter of the park to stop machines from entering. The fences that the university had erected—and people had torn down—now guard a people’s kitchen run by and for the park’s residents. I knelt down to lay my hand on the trunk of one of the dead trees, feeling the moisture of its exposed entrails. Its red sap ran viscous, mixing with the blood from a cut on my hand.

While I was there, there was a conflict in the kitchen, while a small meeting of elder park defenders discussed how long they could go without their medicine if they chose to put their bodies on the line for the park. Rather than interrupting their meeting or the argument by the kitchen, I decided to just add my film screening to the whiteboard calendar at the info table. The habitual worry of not asking the right person or group arose in me, but I wanted the park to be the kind of free place where visitors are trusted to feel and expand the vibe, so I went with it. And I was right: it was that free.

I showed up the next day and an enthusiastic park resident helped me clear tree limbs so I could get our van (both the screen and the power source for our screenings) into the park. With just a day’s notice, a few dozen people showed up. They heard about the event through CrimethInc. social media, word of mouth, and their neighborhood tenant organizing Signal groups. Some authority (we’re unsure whether it was the police, the city, or the university) had cut the power to the park’s street lamps, permitting both the requisite darkness for a film screening in the middle of a city as well as the ambience of urban planning gone wrong.

The audience sat atop a broken excavator covered in graffiti while shooting stars fell overhead and a full moon rose behind the screen. It was perfect. Every feature was about a plaza (Santiago), park (Istanbul), or lot (Atlanta) reclaimed for the people and defended against police.

The discussion continued well after the movies were over:

“Why was there so much more internationalism in the 2019 revolt in Chile than in the George Floyd uprising?”

“How have people in Istanbul kept Gezi park undeveloped after the uprising sparked by the park’s defense was over?”

“You focused on the spontaneity of the revolt in Chile, but was there any role for planning and imagining a new society that guided it?”

The last question highlighted the importance of places like People’s Park for revolutionaries. In the 2019 uprising in Chile, the people’s rejection of the metro’s fare-hike, martial law, and the president was swift, destructive, and memetic. The most important task at the beginning of the uprising was spreading destruction as far and wide as possible. With the widespread destruction throughout Santiago, it quickly became apparent which areas police and troops had capacity to respond to, and which they didn’t. The spaces and times that no authority had the capacity to respond to then belonged to the people. In that autonomy, any model of collective, territorial resilience in defiance of police and other authority spread like wildfire, whether it was student occupations or landless shanty-dwellers taking a plot. Methods of decision-making, slogans and visions, and a spirit of total freedom that had once been relegated to discrete causes or spaces began to flow through all of society and into these newly liberated spaces. It felt like that spirit could fill the entire world.

We hope that this poster helps unleash the revolutionary spirit of Rosebud and the decades of struggle that have kept People’s Park free.

Living, breathing examples of free spaces that have triumphed against police and developers are crucial in revolutionary times, and People’s Park is one of those.

Go to People’s Park. Fill it with free activity and joyous encounter. Bring gifts. Bring plans. There’s still a stage, so make music. Kiss under a tree. Meditate in a quiet corner. Share the good stuff. Tend to plants in the garden. Grill it up. Beautify and build defenses. Prepare to keep the park free from police, construction, boredom, and normalcy. As one enormous banner proclaimed on New Year’s Eve in the Chilean uprising, “We only advance through struggle.”

Further Reading

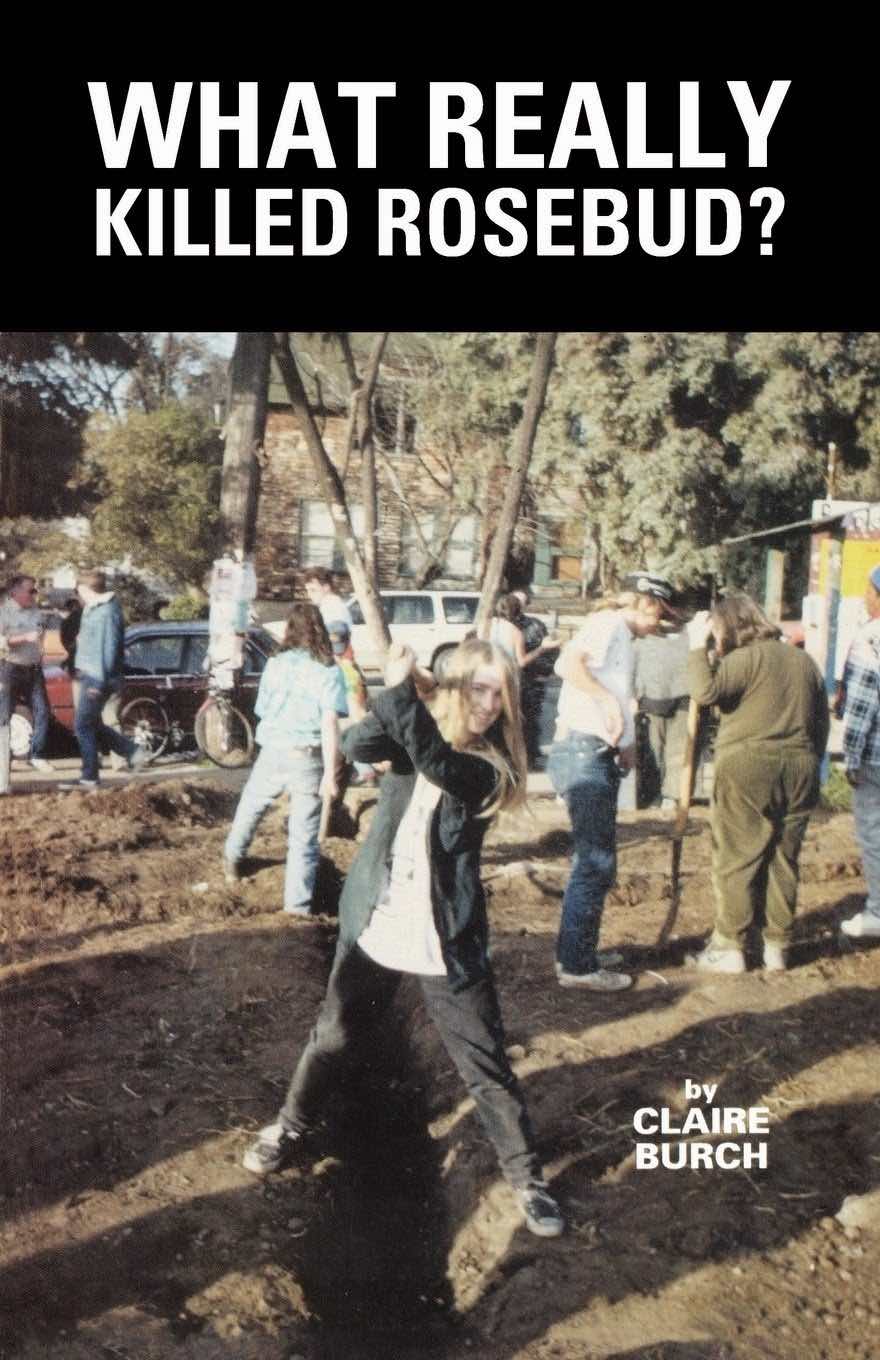

Click the image to download the zine.

Courtesy of Chronotype Imprint, this zine is a collection of excerpts of interviews with Rosebud’s friends, lovers and accomplices during her time fighting for and living in People’s Park. Everything is selected from the book What Really Killed Rosebud? by Claire Burch.

You can read What Really Killed Rosebud? by Claire Burch here.

-

Just yesterday, the prosecutor in Atlanta dropped all charges against the police who murdered Rayshard Brooks, showing once again that any consequences for police murderers will have to emerge from outside the judicial system. ↩